Post #3: The Artist (Part II)

Upon arrival in Chicago, Inukai stayed briefly with a friend from Mark Hopkins and quickly got a job as a janitor, then as a “bellboy” at a hotel, with the goal of affording tuition at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). He enrolled in 1906, initially receiving “free” tuition in exchange for cleaning classrooms. A short time later, once his talent was made apparent, SAIC offered him a full scholarship if he would agree to surrender all works completed while studying there, which he accepted.

The largest art school in the country at the time, SAIC was known for its rigorous curriculum and was considered progressive for its time, enrolling twice the number of women to men and hiring female faculty. The school also admitted many international students and eventually offered studio classes on non-Western art and techniques, for example, “Japanese Painting.” However, it remained primarily focused on the classical European curriculum (white and western), which was the standard for the time. For example, Inukai and other students would have been required to reproduce paintings by the “Masters,” as a barometer for their likely success in the program. The majority of faculty at SAIC were accomplished and respected artists, who were also trained in classical western techniques, having studied at “the best British, German, Dutch, Italian, and French schools,”.

One teacher in particular, John Vanderpoel, would have a major influence on Inukai’s work and decision to pursue a career in portrait art. Vanderpoel, a Dutch-American artist, is best known as the authority on figure drawing. His book, “The Human Figure,” published in 1907, remains a quintessential text for students today. Vanderpoel was also Georgia O’Keefe’s primary teacher at SAIC, when she attended a year prior to Inukai’s enrollment. Inukai was somewhat of a “star student” at SAIC, exhibiting multiple times at the school’s well-regarded museum, and receiving numerous accolades from his instructors and the administration.

Inukai talks about studying under Vanderpoel in his memoir, however he does not discuss anything in relation to his personal life during his time in Chicago. “Book I” of his memoir ends in 1906 and “Book II” picks up in 1915 after he has already relocated to New York. Most of what is known about his life in Chicago comes from Miyoko Davey’s painstaking research.

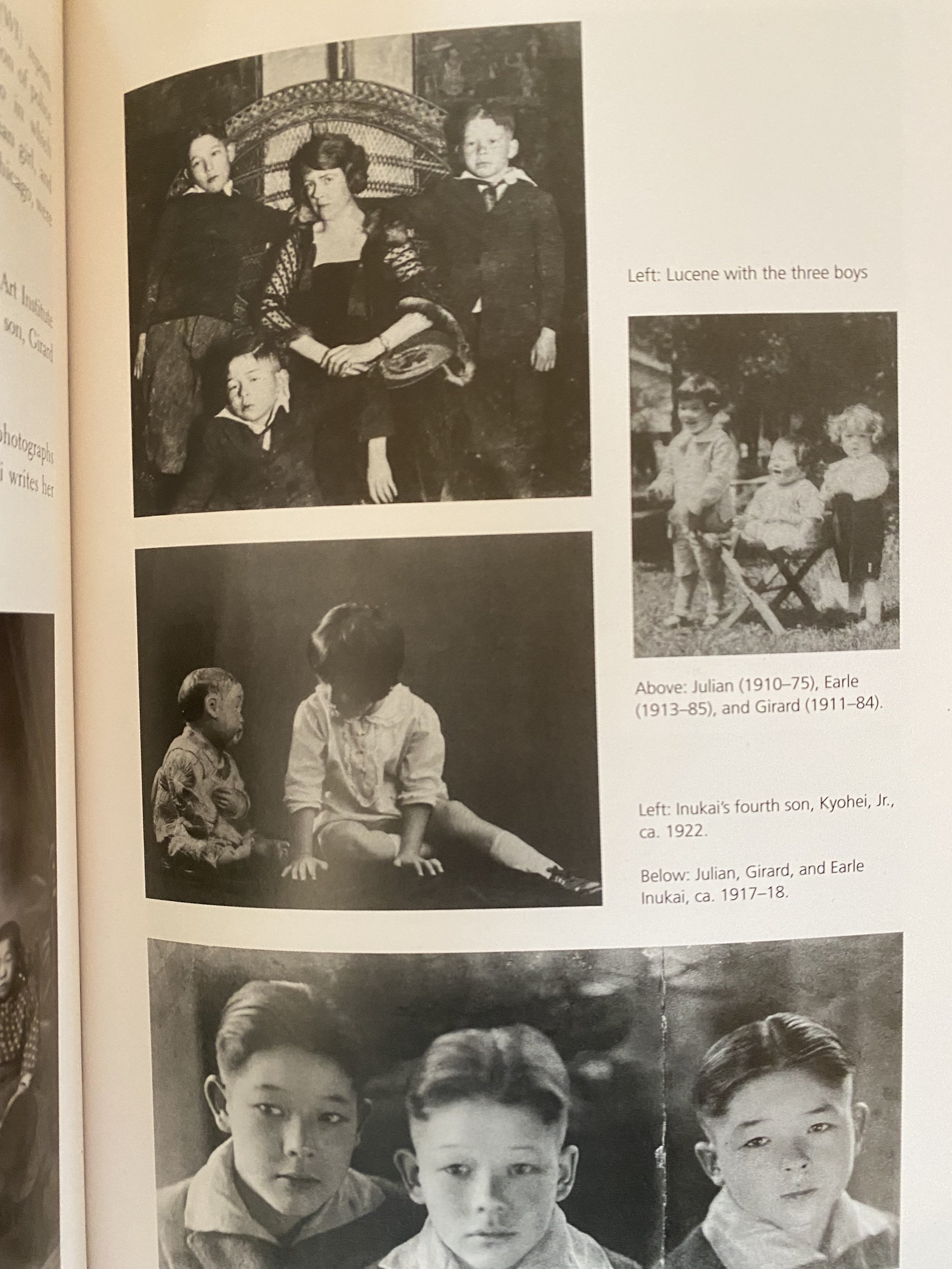

While studying at SAIC, Inukai met fellow student (and future spouse), Lucene Goodenow. Goodenow was known as a talented sculptor, painter, and poet. She was also white and came from a wealthy family in Michigan. They dated for two years, however managed to keep their relationship a secret from other students at SAIC. In a newspaper article, Goodenow is quoted as saying that this was to avoid the rampant “gossip,” however the scandalous nature of a “mixed race” relationship at the time cannot be underestimated.

It was during this period in our history that the racist “Immigration Act of 1917” was passed, essentially barring people from a broad area (extending from the Middle East to Southeast Asia) from entering the U.S. Shortly after, in 1924, the “Asian Exclusion Act” was passed, preventing all immigration from Asia. At the time of Inukai and Goodenow’s engagement, a bill was introduced in the Illinois legislature that, if passed, would render interracial marriage between whites and Asians illegal.

Not surprisingly, given the rampant racism toward Asian-Americans, their engagement and wedding was news-worthy. One headline read, “Chicago Jap to Wed Michigan Society Girl.” The Chicago Evening Journal reported about their relationship on the front page, “Jap Romance Stirs Society.” Goodenow is quoted in one Chicago newspaper, “Even if there is a law against it, we would go to some other state and be married…. We both love art, and are suited to each other.”

Inukai and Goodenow married at her family home in Kalamazoo, Michigan on January 12, 1910. It was reported that her parents initially objected, due to Inukai’s race, but were “won over by his character and brilliant talents,” as well as the fact that he had converted to Christianity. Beyond a scandal, their act of marrying was seriously dangerous, so much so that police were dispatched to the event as a precaution.

In 1910, Inukai and Goodenow’s first son, Julian (1910-1975) was born. They subsequently welcomed two more sons, Girard (1911-1984) and Earle (1913-1985). During this period, Inukai began to experience some success as an illustrator, for both books and commercial advertising. Inuaki and Goodenow remained married for only a few years before separating. In a letter to his daughter later in life, Earle wrote about his parents and upbringing. Regarding their relationship, he shared, “The marriage only lasted a few years, long enough to produce my brothers Julian, Girard and myself. Two artists with ample egos and temperaments were too much to be sustained under one roof.”

It was shortly after his relationship with Goodenow ended in 1915 that he moved to New York City.

Related references & links (post #3):

Wikipedia page for John Vanderpoel

A Family of Artists. Greg Robinson. From Discover Nikkei, July 2021. (This two-part article delves into Inukai’s life, his relationship with Lucene Goodenow, her life, as well as the trajectory of their sons’ careers in art)

Asian Americans Then and Now: Linking Past to Present. From Asia Society.

The next blog post, “The Artist, Part III” will be released on Sunday, May 21.

Black and white photographs of Inukai, Goodenow, and their three children from the book “Kyohei Inukai (1186-1954)” Ed. by Miyoko and John Davey.

Photos from Davey’s book, depicting two of Inukai’s paintings that were exhibited at SAIC while he was enrolled, “Road to Somewhere” (1911) and “Last Glow” (1912).

From Davey’s book, a black and white photo of a newspaper headline, featuring photos of Inukai and Goodenow, reporting on their upcoming nuptials.