Post #4: The Artist (Part III)

According to Miyoko Davey, Inukai most likely wrote his memoir, Confessions of a Heathen, around 1949, three years after WWII had come to an end and when he would have been 63 years-old. As previously noted, there are gaps in time, critical relationships, and events that he chose to omit in the text. His memoir ends abruptly in 1925-26, when he would have been in his early 40’s. This post is the first of two which will chronicle some of what is known about his life in New York City, where he lived until his death in 1954. As a former New Yorker myself, learning about this part of Inukai’s life has been particularly fascinating. It’s funny how simply living in the same place as a complete stranger, more than a century apart, can give you a feeling of connection.

Kyohei Inukai was 29 years-old when he relocated to NYC from Chicago in 1915. He rented a studio apartment in what would now be considered “Midtown.” In the evenings, he would often go onto the roof of the building to escape the summer heat, and this is where he met his second spouse, Willa Kirk (whom he refers to as Olivia Kirkland in his writing, for reasons that are unclear to me). Kirk lived in the same apartment building, was a musician, pursuing a career in opera, and was white. From what I surmise, it was an instant attraction, the kind where you talk until the early morning and can’t fathom how any time has passed at all.

Inukai and Kirk were married in 1917 in Rhode Island. When I met with Davey, I asked her if she had any inklings as to how one of Inukai’s paintings ended up in Maine. She didn’t, however she shared a connection to Maine that I was unaware of. During this time in our country, marriage between “whites” and “Asians'' was illegal in New York. However, there was not a law against it in Maine and this is where Inukai and Kirk traveled to obtain a marriage license. This doesn’t explain how a painting by him, of a child that would be born more than a year into the marriage, would land in an antique store here in Maine, but it is really interesting (for lack of a better qualifier) to ponder.

During this period of his life, Kyohei Inukai came to experience significant commercial success as an illustrator for books and magazines, making $500-600 per week (roughly equivalent to $10,000 today). It cannot be emphasized enough how remarkable it was for a Japanese-American to experience this level of success amidst the vehement anti-Asian sentiment and propaganda that he would have been subjected to.

Also in 1917, Kanokogi Takeshirō (1874-1941), a well-known artist, also from Okayama Prefecture, visited New York. Upon his arrival, he was welcomed by several Japanese-American artists at a dinner in his honor. According to Takeshirō, Inukai was meant to attend but was unable to. However the other artists insisted that Takeshirō find time to visit him at his studio, as he was a “first-class painter of the area.”

Takeshirō did so and ended up staying with him and Kirk for a short period, due to a coal (heating) shortage in the city at the time. After this visit to the US, Takeshirō visited Inukai’s family to “report on his activities.” From what I gather, significant time had passed since Inukai’s family in Japan had received word directly from him. Takeshirō also writes about meeting Inukai in a Japanese newspaper, Chugoku Min’po. The title of the article was, “An Artist Shining in a Foreign Country, Kyohei Inukai of Okayama Prefecture, Reputed as a First Class Painter in the States.” In this article, Takeshirō (clearly impressed) writes, “on leaving for Japan, I left word with him [Inukai]: strive to be a world class master artist, not limiting himself to the states.”

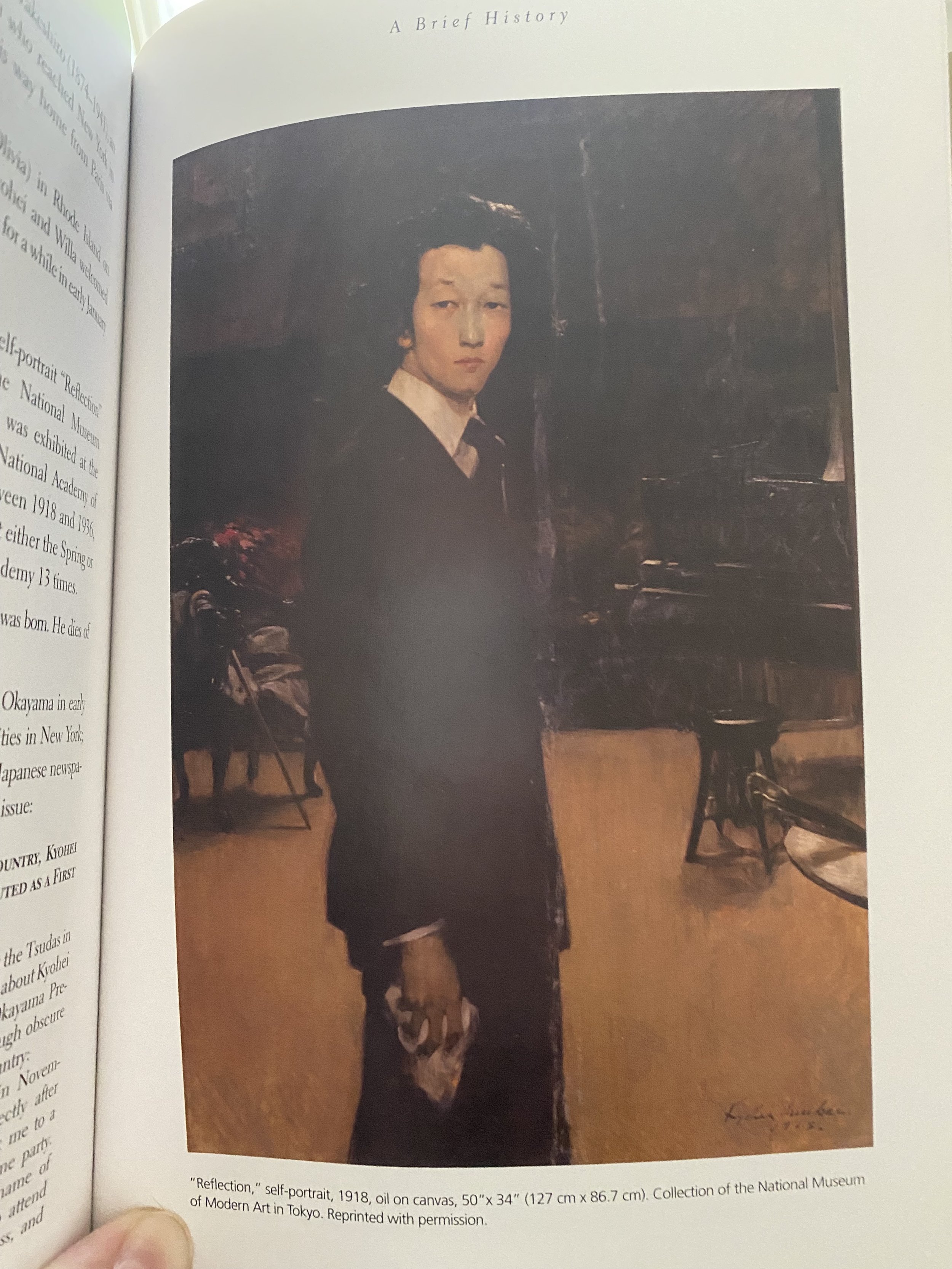

In 1918, at age 32, Inukai completed his self-portrait, “Reflection,” which was exhibited at the National Academy of Design in NYC (I believe in that same year). “Reflection” now resides at the National Museum of Modern Art, in Tokyo. This is around the time in which he writes about wanting to move away from illustration and commercial work to focus on portrait painting.

Later, in 1921, “Reflection” would exhibit at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. Inukai was one of seven artists from this show to be reviewed by Hamilton E. Field, a well-respected artist and art critic of the time, known specifically for his expertise in Japanese prints. Among the other six was John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), a portrait artist who continues to garner international acclaim to this day. If you’re local to Portland, you can view two of his (in my opinion) most beautiful and haunting portraits at the Portland Museum of Art (last I checked). We will revisit Inukai’s relationship to Sargent in later posts.

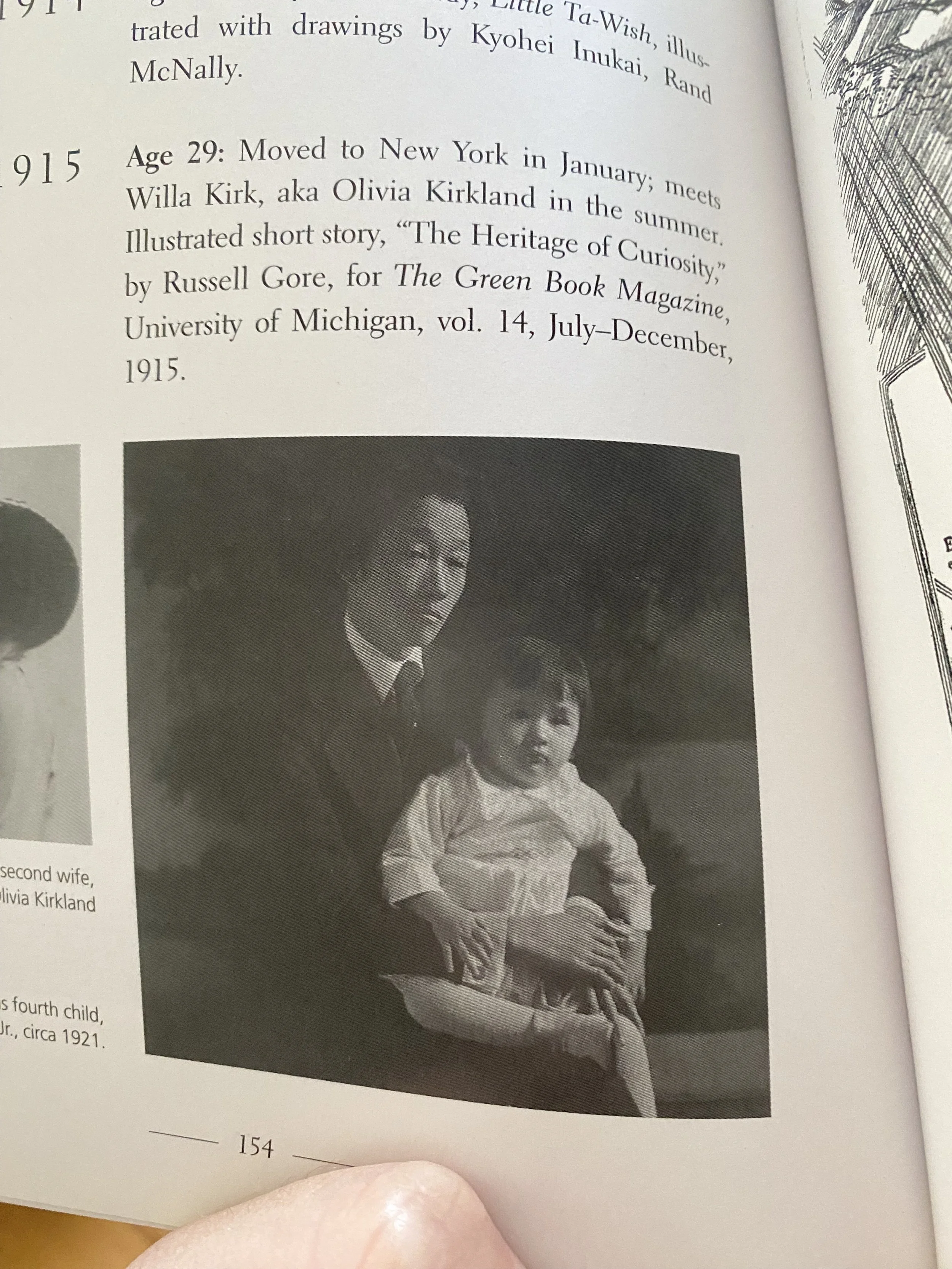

In 1918, the same year that he completed “Reflection,” Inukai and Kirk welcomed a child, Kyohei Inukai, Jr. This is the child, clutching a black cat, who is depicted in the painting that I purchased.

Related references & links (post #4):

Wikipedia page for Kanokogi Takeshirō

Wikipedia page for John Singer Sargent

National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo: “Reflection”

A photo of “Reflection” (1918) from “Kyohei Inukai” Ed. by Miyoko and John Davey

A photo of a photo of Olivia Kirkland from “Kyohei Inukai” Ed. by Miyoko and John Davey

A photo of a photo of Inukai, Sr. holding Inukai, Jr. on his lap, from “Kyohei Inukai” Ed. by Miyoko and John Davey

A photo of the portrait I purchased, painted by Inukai, Sr. of his son, Inukai, Jr.